Lester Frank Ward

June 18, 1841 — April 18, 1913

I have always maintained that sociology is a science of liberation and not of restraint.

L. F. Ward, Pure Sociology (1914)

Biography

The Ward family moved from Illinois to Myersburg, Pennsylvania while Frank was still a boy. By day Ward joined his brother Cyrenus in their hub, or wagon wheel, shop. By night he devoured books and developed a craving for knowledge and study. Some believe that Ward’s childhood spent in poverty, followed later by hard labor in the wagon shop, instilled in Ward an outrage at society’s injustice and inequalities.

In the early 1860’s Ward attended classes at the Susquehana Collegiate Institute in Towanada. On August 13, 1862 he married Elizabeth “Lizzie” Caroline Bought (some sources give her name as “Vought”). When the Civil War broke out, Ward joined a local Pennsylvania regiment and was seriously wounded at Chancellorville. Like many soldiers away from home to fight in the war, Ward kept a journal. This journal, which was found many years after his death, was published (and is still available today) under the title, Young Ward’s Diary: A Human and Eager Record of the Years Between 1860 and 1870 as They Were Lived. Some of his thinking about society and inequality developed further during his Civil War experience and the years that followed.

After the war he began working for the federal government while continuing his self-education. From 1865 to 1881 Ward was employed by the United States Treasury Department. After many years of saving and waiting, Ward finally fulfilled his dream when he started to study at Columbian College (now The George Washington University) from which he received the A.B. degree in 1869, the LL.B. degree in 1871, and the A.M. degree in 1872.

In 1882 Ward was appointed Assistant Geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, a post he held for two years. He served the USGS for the remainder of his career in the federal government, receiving promotions to Geologist in 1889, and Paleontologist in 1892.

In addition to his USGS work, Ward was appointed Honorary Curator of the Department of Fossil Plants in the US National Museum in 1882. He remainded in charge of the national collections of fossil plants until his retirement from the USGS in 1905.

After a career in the federal government, Ward embarked upon a new career. In 1905 he wrote to James Quayle Dealey of Brown University to inquire about the possibilty of teaching at Brown. Dealey responded favorably. After negotiations with the University’s President, William Faunce, Ward was offered a teaching position in late 1905. He moved to Providence in the fall of 1906. Rafferty described Ward’s move: “Ward’s arrival at Brown University was to be the climx of his tellectual career, the highlight of a long journey studying and writing about social and scientific subjects.”

Ward is best remembered for his pioneering work in sociology. Between 1883 and his death in 1913, he completed several important works including Dynamic Sociology (1883), Outlines of Sociology (1898), Pure Sociology (1903), and Applied Sociology (1906). Ward’s most important contribution to sociology was his insistence that social laws, once identified, can be harnessed and controlled.

Ward supported the idea of equality of women as well as the equality of all classes and races in society. He believed in universal education as a means of achieving this equality. Many of his ideas were unpopular among his male contemporaries, but would probably play better to an audience today.

In the summer of 1905, Ward and a number of prominent colleagues began corresponding with sociologists around the country about the possibility of forming a new society specifically for sociologists. In December 1905, as part of the Annual Meeting of the American Economics Association, Ward and others met in Baltimore to debate the issue. Ultimately they acted to form a new society, the American Sociological Society. Ward was surprised when he was selected to serve as the first President of the new society for 1906 and 1907.

As President of the American Sociological Society in 1906 and 1907, Ward gave an address at the annual meeting of the society each year:

- December 27, 1906 – “The Establishment of Sociology”

- December 28, 1907 – “Social Classes in the Light of Modern Sociological Theory”

Beginning in 1911, Ward’s health was in decline. He continued working and teaching until shortly before his death in Washington, DC on April 18, 1913.

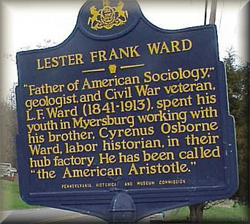

In Ward’s boyhood home of Myersburg, Pennsylvania, an historical marker stands today in honor of his roots and his contributions to sociology:

I am an apostle of human progress,

and I believed that this could be greatly accelerated

by society itself.”

–Lester Frank Ward

To learn more about Lester Frank Ward, check out the following items and resources:

- Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7321 – Lester Frank Ward Papers, 1882 – 1913, with Related Materials to Circa 1965.

- Upon his death in 1913, Ward willed his personal library and many of his papers to Brown University. The Ward materials at the John Hay Library at Brown University in Providence, RI (MS 90-23) encompass about 5,400 items including scrapbooks and portfolios of personal papers, notes, transcripts, and proofs of published works, and a diary in French (1860-1869). This group is individually catalogued. Correspondence (1865-1913) includes about 5,800 items chiefly to Ward concerning professional matters. Less than half of this group is catalogued individually; the remainder being accessible through a register. The two main series, the correspondence and the writings, are available on microfilm. The latter series is subdivided into unpublished writings and manuscripts of published monographs.

- Barnes, Harry Elmer. “Two Representative Contributions of Sociology to Political Theory: The Doctrines of William Graham Sumner and Lester Frank Ward.” The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Sep., 1919), pp. 150-170.

- Burnham, John C. “Lester Frank Ward as Natural Scientist” American Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Autumn, 1954), pp. 259-265.

- Burnham, John C. 1956. Lester Frank Ward in American Thought. Washington DC: Public Affairs Press.

- Cape, Emily P. 1922. Lester Frank Ward: A Personal Sketch. New York: Putnam.

- Chugerman, Samuel 1939. Lester Frank Ward, The American Aristotle: A Summary and Interpretation of his Sociology. Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press.

- Commager, H.S., ed. 1967. Lester Ward and the Welfare State. New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Dealey, James Q. et al. “Lester Frank Ward.” The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Jul., 1913), pp. 61-78

- Dealey, James Quayle. “Masters of Social Science: Lester Frank Ward.” Social Forces, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Dec., 1925), pp. 257-272.

- Finlay, Barbara. “Lester Frank Ward as a Sociologist of Gender: A New Look at His Sociological Work.” Gender and Society, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Apr., 1999), pp. 251-265.

- Fleming, James E. “The Role of Government in a Free Society: The Conception of Lester Frank Ward.” Social Forces, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Mar., 1946), pp. 257-266.

- Gillette, John M. “Critical Points in Ward’s Pure Sociology.” The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Jul., 1914), pp. 31-67.

- Largey, Gale P. Lester F. Ward: A Life’s Journey. 2005. This is an excellent 108-minute DVD that documents the life and ideas of Ward.

- Mihanovich, C. S. “Ward’s Educational Theories.” Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Nov., 1946), pp. 140-153.

- Nelson, Alvin F. “Lester Ward’s Conception of the Nature of Science” Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Oct., 1972), pp. 633-638.

- Rafferty, Edward C. Apostle of Human Progress: Lester Frank Ward and American Political Thought, 1841-1913 (American Intellectual Culture Series), 2003.

- Rice, Stuart A. “The Spirit of Ward in Sociology.” Science, New Series, Vol. 84, No. 2174 (Aug., 1936), pp. 192-194.

- Small, Albion W. et al. “The Letters of Albion W. Small to Lester F. Ward.” Social Forces, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Dec., 1933), pp. 163-173.

- Stern, B. J., editor. 1935. Young Ward’s Diary: A Human and Eager Record of the Years between 1860 and 1870 as They Were Lived in the Vicinity of the Little Town of Towanda, Pennsylvania; In the Field as a Rank and File Soldier in the Union Army; and Later in the Nation’s Capital. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1935 (first edition).

- Stern, B. J. 1938. “The Ward-Ross Correspondence.” American Sociological Review 3:362-401; 1946, 11:593-605; 1947, 12:703-20; 1948, 13:82-94; 1949, 14:88-119.

- Stern, Bernhard J. “The Liberal Views of Lester F. Ward” The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 71, No. 2 (Aug., 1950), pp. 102-104.

- Ward, Lester F. “Feeling and Function as Factors in Human Development.” Science, Vol. 1, No. 17 (Oct., 1880), pp. 210-211.

- Ward, Lester Frank. 1881. Guide to the Flora of Washington and Vicinity.

- Ward, Lester F. 1883. Dynamic Sociology. New York: Appleton.

- Ward, Lester F. “Mind as a Social Factor.” Mind, Vol. 9, No. 36 (Oct., 1884), pp. 563-573.

- Ward, Lester F. “Why Is Water Considered Ghost-Proof?” Science, Vol. 5, No. 100 (Jan., 1885), p. 2.

- Ward, Lester F. “The Ginkgo-Tree.” Science, Vol. 5, No. 124 (Jun., 1885), pp. 495-497.

- Ward, Lester F. “A Convenient System of River Nomenclature.” Science, Vol. 6, No. 140 (Oct., 1885), pp. 321-322.

- Ward, Lester F. “A National University, Its Character and Purpose.” Science, Vol. 18, No. 459 (Nov., 1891), pp. 281-282.

- Ward, L.F. 1892. The Psychic Factors of Civilization. Boston: Ginn.

- Ward, Lester F. “The Nature of Pleasure.” International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Oct., 1897), pp. 100-101.

- Ward, Lester F. 1903. Pure Sociology. New York: Macmillan.

- Ward, Lester F. “The Pteridospermaphyta.” Science, New Series, Vol. 20, No. 496 (Jul., 1904), pp. 25-26.

- Ward, Lester F. “An Example in Nomenclature.” Science, New Series, Vol. 21, No. 525 (Jan., 1905), pp. 110-111.

- Ward, Lester F., “Social Class in the Light of Modern Sociological Theory.” The American Journal of Sociology, vol. xiii (March, 1908).

- Ward, Lester Frank. Glimpses of the Cosmos: A Mental Autobiography. 1913-1918 (6 volumes):

Vol. I, Adolescence to Manhood

Vol. II, Scientific Career Inaugurated

Vol. III, Dynamic Sociology

Obituary

Written by James Q. Dealey, published alongside other remembrances in The American Journal of Sociology, 1913.

The men who are best qualified by their debt to Professor Ward, and by their consciousness of it, to form a just estimate of his works, shrink from the responsibility of attempting immediately a formal appreciation of his meaning for sociology. While it is too early for the estimate, at once critical and comprehensive, which those to whom Dr Ward has been preceptor and mentor, hope to put on record after due deliberation, the following tributes will sufficiently mark the place which he has occupied in the esteem of his colleagues, among whom his primacy was always uncontested.

Professor Ward’s connection with Brown University came about in a perfectly natural manner. The department of Social Sciences was deeply interested in his sociological theories and when his Pure Sociology first came from the press, seized the opportunity of using it as a textbook for an undergraduate class. The members of it survived but still speak in bated breath of their experience in completing the book in thirty lectures. Interest in Pure Sociology resulted in a, simplified edition of it in 1905, The Text Book of Sociology. When, a little later, Dr. Ward in conversation expressed a desire to resign from governmental service in order to devote several years to literary work, a suggestion from the department to President Faunce met with his hearty sanction, so that in the fall of 1906 a new professor of sociology at Brown modestly introduced himself to his classes.

Throughout his seven years of service Professor Ward conducted three elective classes of upper classmen and graduates, easily winning their esteem and stimulating the zeal of those students eager for a broad outlook over the sociological field. In the performance of his duties he was faithful in the extreme, and impressed all by his keen intellectuality and his enormous capacity for work. As his avocations he studied the geology and botany of Rhode Island, often taking long walks of ten to fifteen miles in length. Outside of the preparation of his lectures, the material of which he planned at some time to put into book form, his chief literary task was the preparation of the manuscript for his unique collection of twelve volumes now on the eve of publication. This great task occupied him for the better part of four years and was finally completed, even to the index, less than a year ago.

He was so absorbed in his labors that his life was necessarily a secluded one. In social intercourse, however, he was always genial and kindly, and constantly showed a deep interest in the intellectual developments of the time and the newer discoveries in the several departments of science. Owing to the illness of his wife, he spent his last four years in a college dormitory, and thereby became more closely identified with the life of the campus. This experience he thoroughly enjoyed and he became in consequence deeply attached to the university.

The news of his unexpected death brought great sorrow both to city and college. For three days the university flag was at half-mast, and at the time of his funeral the college bell was tolled and classes were suspended. The Providence Bulletin of April 19, in speaking editorially of him said:

A DISTINGUISHED BROWN SCHOLAR

In the seven years of his connection with the faculty of Brown University, Dr. Lester Frank Ward, who died in Washington yesterday, became a familiar figure in Providence. Of a rather unusual personal presence, he was frequently seen on the streets of the city, though most of those who noted him in his after- noon walks were unaware that he was one of the most distinguished scholars of his day and generation.

Dr. Ward was a close student, a keen observer, a prolific and perspicuous writer. He received many honors abroad as well as in this country, among them election to the presidency of the International Institute of Sociology, a body to which only a very few Americans have ever been chosen. Withal he was a man of great modesty and kindliness, and endeared himself to his students by his ability to reach their point of view and his willingness to do all in his power to assist them.

Brown University has been honored by his seven years association with its teaching force, and is measurably poorer by reason of his passing.

On June 3 the faculty of the university placed on their records the following minute in his honor:

The members of the faculty of Brown University, desirous of expressing their deep sorrow at the loss of their esteemed colleague, Professor Lester Frank Ward, hereby place on record their appreciation of his sterling character and scholarly attainment. Coming to us near the close of a long life of severe mental exertion, he brought with him the mature results of his studies and undiminished ardor in their pursuit. His labors in botany, geology, and paleontology had been crowned with success, and his pioneer work in sociology had given him a world-wide reputation. He was a profound student, and an original investigator in the most abstruse problems with which the human mind can grapple. For seven years the faculty and students found in him a genial associate, an inspiring teacher and a sincere and unflinching seeker after truth.

From the very start Professor Ward attracted the attention and devotion of his students. At the end of his first year a loving-cup was presented to him by his classes; an undergraduate philosophical society made him a member; the Liber, an annual undergraduate publication, was dedicated to him in 1912; and at the announcement of his death the students voluntarily contributed a large sum for flowers to be placed on his grave. The feeling his classes held for him is well .shown in the following contribution from Charles Carroll, a candidate for the Master’s degree:

“Every genius is a child; every child a genius.” These were almost the closing words in Dr. Ward’s last lecture at Brown University. In a sense they describe the man himself-a genius with the simplicity of a child-that glorious simplicity which the Saviour of the world had in mind when he said: “Unless ye shall become as little children.” But in Dr. Ward it was the simplicity which comes from great knowledge, from the possession of truth; that mental calmness which must arise from a complete philosophy of life. -Such are his works. In the classroom Dr. Ward impressed the student as a final authority; he seemed to know everything, from the beginning until the final destruction of the world. Logic flowed in his words like the gentle current of a country brook in midsummer. There was no turbulence, no strain, never a hiatus. Thought fitted into thought, each succeeding step resting upon the previous in perfect filiation, building always upward and onward. Every lecture was a recapitulation of evolution; not that tremendous striving of nature, with its waste and failures, its trials and errors, its barbarous natural selection; but the superior artificial selection which charms the reasoning mind of man. From the solemnity of great thoughts, from the simple statement of universal truths, fundamental yet transcendental in their importance, the class was called back by occasional bursts of genuine humor. The gentle Doctor was himself trans- formed, his face lighted up, his eyes sparkled-one might at such moments imagine what sort of man Dr. Ward had been in his earlier years-for he was old when he first came to Brown University. Old but not decadent, aged but still active; his mental vision as clear as in his prime. Only the body of Dr. Ward had yielded to time, his mind was still fresh and an inspiration to his students.

For more writings on Lester Frank Ward, please see the American Journal of Sociology. 19(1):61-78. (1913).